In the late 6th cent. BC the sanctuary was expanded to the north, thus doubling the area the Archaic peribolos enclosed. A new temple, identified as the Temple of Triptolemus, was erected in the middle of the new peribolos, over an area up to then taken up by private residences (Miles 1998, 28 n. 13, contra Travlos 1971, 198).

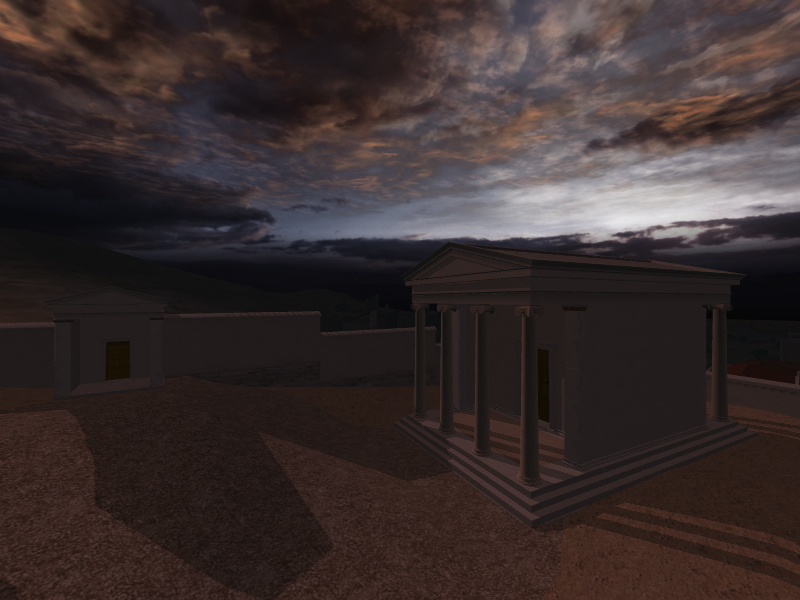

1. The Temple of Triptolemus

The temple rests on a foundation measuring 11.065 × 17.813 m and has a north-south orientation, parallel to the course of the Panathenaic Way. The southwest corner of the temple crossed through the line of the original north wall of the Archaic peribolos and crossed into the temenos of the Archaic period. According to Miles (1998, 35) this was intentional, in order to secure the continuity of the sacred precinct with the earlier temenos, as the temple was built over the ruins of private residences of the Archaic period. Correspondingly, the selection of an north-south axis (instead of the customary east-west one which was usually implemented in Greek temple building) was not dictated by the terrain, but was perhaps intentional, maybe because of the general demarcation of the sanctuary's area vis-à-vis the Agora and the Panathenaic Way.

The temple’s foundations are made up of good quality grey poros stone, cut in polygonal blocks. Following the completion of the foundations, a second layer of blocks, of reddish poros stone, was added along the east side of the building, thus altering the proportions of the foundation and, consequently, those of the temple. Due to the terrain’s downward gradient, on the south side the euthenteria rests on the dug out natural bedrock, while on the north at least ten files of blocks were needed to restore its horizontal position (see Miles 1998, 14 pl. 3). Later, in the 4th cent. BC, a second, larger retaining wall was added north of the temple (Miles 1998, 38 and 14 pl. 3).

The enlargement of the foundations indicates that the building’s design was altered during its construction. The width of the building was thus increased by 2.35 m (on a total final width of 11.05 m). The original foundation (8.71 × 17.813 m) was designed based on a width/length ratio of 1:2. With the addition of the 2.35 m this ratio approximates the ‘Golden Ratio’ (1:√5/2), which was quite often used in temples of Greece and Sicily and Lower Italy, especially in the late 6th and the early 5th cent. BC (Miles 1998, 38 and pl. 6).

The Temple of Triptolemus dates to the second quarter of the 5th cent. BC based on the following excavational and other data:

· the demolition of pre-existing residences in the site towards the end of the 6th cent. BC

· the commencement of construction works on the foundation in the 500s BC

· the stylistic analysis of the surviving roof tiles, made up of island marble, including the anthemia-decorated antefixes (the only surviving members of the temple’s superstructure)

· the historical circumstances, i.e. the Persian Wars and the destruction of Athens by the Persians in 480 BC

· an indirect epigraphical testimony (Miles 1998 Cat. Ι, 44), according to which the architect Coroebus, also mentioned by Plutarch as one of the architects of the Telesterion of Eleusis (Plut, Per. 13.7), was probably commissioned to construct the Temple of Triptolemus in the Eleusinion en astei, as well as the Temple of Demeter and Kore in the same sanctuary, which is mentioned by Pausanias (1.14.1) and epigraphical testimonies (Miles 1998 Cat. Ι, 35) but remains unknown to scholars (possibly because it was located in the inaccessible today east part of the sanctuary: see Miles 1998, 43-43).

Although formerly certain scholars believed that the Temple of Triptolemus featured no colonnade, its latest pictorial representation, by M. Miles and R.C. Anderson, suggests a tetrastyle amphiprostyle temple in the Ionic order (on the basis of the proportions of the foundation, its marble roofing and similarities to other comparable temple-like structures of the period) constructed exclusively of marble (Miles 1998, 43-48, pl. 6-7).

1.1. The identification of the Temple

Two passages in Pausanias (1.14.1 & 1.14.3-4) refer to the Eleusinion en astei and the Temple of Triptolemus. From these we can gather that “above” (i.e. southeast) of the “fountain” (i.e. the Enneakrounos fountain) stood the: a) Temple of Demeter and Kore and b) the Temple of Triptolemus. Pausanias states that he is unable to describe the former, in the “inner part”

of the sanctuary, (he was forbidden to do so by an “apparition in a dream”). On the contrary, he declares that he will treat the monuments accessible to all, i.e. those towards the Temple of Triptolemus, in front of which a “statue of Triptolemus stands, and a bronze bull, as if lead to a sacrifice, has been set up, as well as a seated statue of the Cnossian Epimenides”.

We may deduce, therefore, that the temple that has been excavated in the sanctuary was dedicated to Triptolemus and that the sanctuary was divided into an 'inner’ section, closed off to the crowds (and today buried under the modern city), and an ‘outer’ section accessible to all. Those about to be initiated to the mysteries gathered in the ‘outer’ peribolos, while the mystical rituals were performed in the ‘inner’, protected peribolos (Miles 1998, 44 & 48-52).

1.2. Sculptural decoration

The statue of Triptolemus mentioned by Pausanias (1.14.1,4) has not survived. It is believed, however, that it is depicted on Panathenaic amphorae, where the theme of Triptolemus was more popular than those of Nike and Athena (according to one scholar the specific statue had been selected as the emblem of the games, following a decree of the Boule, in three different Panathenaic festivals). As the Eleusinion was located close to the finish line of the apobasis contest (a chariot race which also featured simultaneous exercises by armed men jumping from moving chariots) the statue of Triptolemus, also visible from the Panathenaic way, had become associated with the Panathenaic festivities, like other sculptures of the Agora (e.g. the Tyrannicides). The statue Pausanias saw in 150 AD would have been set up before 364 BC (the date of its first appearance on the relevant amphorae); it may also be the object of an even earlier representation found on a pottery shard dating to 410-400 BC (Miles 1998, 52 and n.44 & 46. Cf. Eschbach 1986).

The bronze statue of the bull mentioned by Pausanias (1.14.4) is probably referred to in a votive inscription of 440-420 BC from Eleusis, where it is specified that Triptolemus and other divinities should receive as sacrificial offering a bull with gilded horns.

The seated statue mentioned by Pausanias in the same passage (1.14.4) represents a mythical (or for some a historical) figure mentioned by Plato and other ancient authors: Epimenides, a seer from Cnossus; he fell asleep in a cave for forty years and then went on to compile poetry and purified Athens after the pollution it had befallen upon the city following the perfidious killing of Cylon in the late 7th cent. BC.

2. 5th – 4th c. BC

A large retaining wall was built 4 m north of the Temple of Triptolemus in the 4th cent. BC (Miles 1998, pl. 8). The wall consists in six blocks of soft poros stone and is 3-4 m thick.

North of the north-western corner of the 5th cent. peribolos architectural remains have been identified, perhaps belonging to another temple, probably of Hecate, which was constructed in this spot during the 5th cent. BC and was relocated to a place more to the north in the mid-4th cent. BC, when the Panathenaic way was redrawn and moved further to the east.

The entrance to the sanctuary in the Classical period was in the south, close to the south-western corner of the peribolos (see Miles 1998, 58 pl. 8). A small Propylon was constructed at this spot, in the third quarter of the 4th cent. BC. During the same period a second entrance to the sanctuary was built, also along the south peribolos, 20 m approx. east to the Propylon, and very close to the fringes of today’s archaeological site.

A large number of votive offerings, mainly statues and inscriptions, adorned the open air spaces of the sanctuary from the 5th cent. BC to the 2nd cent. AD (according to the excavational finds: see Miles 1998, 64-68 and table 2). The earliest votive offering, a base (probably) for a Hermaic stele (Miles 1998, 66 and Cat. Ι,1) mentions a prothyron in the area of the sanctuary, possibly a propylon between the ‘outer’ and ‘inner’ sanctuary. The sculptures mentioned in the surviving inscription bases, as well as surviving fragments, originate from portraits of priestess or depictions of Demeter and Kore. Votive sculptures, set up in honour of the two Eleusinian deities, as well as of Triptolemus and Hecate, Iacchus, Eubouleus and Pluto also survive. Fragments from thirty votive inscriptions, mostly honorific, have also been unearthed.

3. The ‘Attic Stelae’

In 415/4 BC, on the eve of the launch of the fateful for Athens Sicilian Expedition, a huge religious scandal broke out in the city, an affair which had political repercussions: the heads of the Hermaic stelae of the city were found mutilated and rumours circulated that during a symposium the banqueters had parodied the Eleusinian mysteries. Accusations were hurled against Alcibiades, who was eventually sentenced to have his property confiscated by the state (Thuc. 6.27-29; Plut. Alc. 22.4). Alcibiades’ and his co-defendants’ property was sold off, and the sums that were collected were posted on ten inscriptions ('Attic stelae’) set up in common view in the area of the Eleusinion (Poll. 10.97), from which the 66 out of the 77 known today fragments of these stelae originate (Miles 1998, 65-66).